„PAWNS OF TRAGEDY IN UKRAINE./Fund No. 2000. op. 2, case 131, pp. 143-144“,

oil on canvas, 100x130cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

„Distress signal.

I write from the depths of the countryside, where fate cast me by chance during the time of crop sowing. I consider it a crime to remain silent about what I see every day.

In the village of Danilova-Balka, the grain harvesting plan has been OVERDONE.

I will speak of that which everyone should turn their attention to - the material situation of the collective farmers and their families.

While carrying out a vaccination campaign against typhoid and smallpox, every day I go from house to house in the village and witness horrible imagery. Empty houses with many children inside bearing pale faces, with unchildlike serious sad eyes, with thin arms and legs. The children are hungry. They feed on rotten roasted beets that have overwintered in the field.

Most of the collective farmers themselves are exhausted, most are bloated with hunger. They move like shadows.

Bread in the collective farm, even during sowing, is not handed out. There is no public catering, but it is needed here. I will not look for the reason behind this severe plight of the collective farmers, I write only to bring attention to it and aid while there is still time. There are still 4-5 months until the harvest, and there is little hope that the children, and many adults, will survive.

In the outpatient clinic, a patient turned to me and said - "give me a piece of bread", and I myself had spent 20 days without bread, because the director of the Machine-Tractor Station refused to give the deployed doctor food, and it is not possible to buy bread in the market, as the selling of bread is prohibited.

The village is doomed to extinction.

Almost every day I receive instructions from the Regional Health Department for the storage of meat products, for special clothing, for the storage of bread. The regional health department is located 45 km from Danilova-Balka. Do they really not know that there has been no bread and meat in Danilova-Balka for a long time. Of course, I will not talk about the Machine-Tractor Station, where the employees are in a special position.

Temporary manager of outpatient clinic (seeding campaign). Doctor – Mingaleva.“

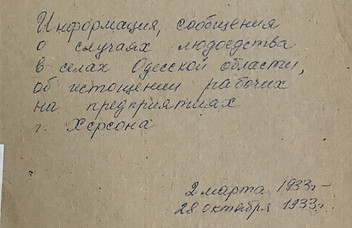

„P-470. op. 2, file 2. Information, reports on cases of cannibalism in the villages of Odesa region, on the exhaustion of workers at enterprises in the city of Kherson. 02.03.1933 - 28.10.1933. №20“,

oil on canvas, 90x130cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

„On the night of February 28, 1933, in the village of Leontovichevo, in the family of Vasilenko, expelled from the Labor Cooperative farm for stealing bread during the harvest and sentenced to 10 years in prison, there was a case where a 15- year-old boy strangled a 4-year-old child.

After strangling the child, he woke up the other children, aged 12, 8 and 6, and invited them to cut him up for consumption.

As the younger children were frightened by his proposal, he immediately took an axe and chopped the child to pieces, laid him in bed and salted him.

In the process, he took out the heart, liver and lungs, fried them and fed the rest of the children.“

.png)

„GARETH JONES“,

oil on canvas, 110x130cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

‘THERE IS NO BREAD’

Gareth Jones Hears Cry of Hunger All Over Ukraine

And Then a Second Phrase Occurs: “We Are Swollen,” Victims of Famine Complain

By Gareth Jones:

“I walked along through villages and twelve collective farms. Everywhere was the cry, 'There is no bread. We are dying. I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening. In the train a Communist denied to me that there was a famine. I flung a crust of bread which I had been eating from my own supply into a spittoon. A peasant fellow-passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw an orange peel into the spittoon and the peasant again grabbed it and devoured it. The Communist subsided.

„You’re hungry“ - I said to him. „Hungry“ - he replied. „We peasants are all hungry. The Communists took away our grain. They robbed us of our land. They came to our village and left only a few potatoes for us to live through the Winter. There’s bread in the big cities, but there is no bread in the villages in the homes of the people who grow the wheat.“

“A great multitude that no man could number”,

oil on canvas, 90x120cm, 2010, Yona Tukuser

BY GARETH JONES:

“The snow lay deep around as I began my tramp through the villages of the North Ukraine, the part of Russia which once fed Europe and was known as the granary of the world.

I decided therefore to walk along the railway tracks, for if I penetrated into the country I should be lost in the snow and perhaps never return.

The first words I heard were ominous, for an old peasant woman moving with difficulty along the track answered my greeting with that phrase, “Hleba nietu” (“there is no bread”). “For two months we have had no bread here,” she added in that deep crying voice which most of the peasant women had. “Many are dying in the village. Some huts have potatoes, but many of us have only cattle fodder left, and that will only last another month.”

Yes, famine was raging in that village as it was throughout that district.

“Famine!” said the old men who assembled to talk to me in the bare hut. “It’s famine. Worse even than in 1921.

“You ask how many people have died? We cannot tell. We have not counted them, but perhaps one in every ten.

“And death is on the way to this village for many of us, because it is some months before the next harvest.”

Long into the night the discussion continued of how the Communists had brought ruin to the countryside by their policy of taking the land and the grain and the cow away from the farmer, and it was long before I fell asleep, in the middle of a famine-stricken village.”

‘REDS LET PEASANTS STARVE’,

oil on canvas, 90x130cm, 2010, Yona Tukuser

„BY GARETH JONES:

“The Communists came and seized our land, they stole our cattle and they tried to make us work like serfs in a farm where nearly everything was owned in common” – the eyes of the group of Ukrainian farmers flashed with anger as they spoke to me – “and do you know what they did to those who resisted? They shot them ruthlessly.”

I was listening to another famine-stricken village further down the icy railroad track which I was tramping and the story I now heard was one of real warfare in the villages.

The peasants told me how in each village the group of the hardest-working men – the kulaks they called them – had been captured and their land, livestock and houses confiscated, and they themselves herded into cattle trucks and sent for a thousand or two thousand miles or more with almost no food on a journey to the forests of the north where they were to cut timber as political prisoners.

The Communists I spoke to did not deny that they had ruthlessly exiled the hardest working farmers.

On the contrary they were proud of it. “We must be strong and crush the accursed enemies of the working class,” the Communists would say to me, “Let them suffer now. We have no place for them in our society.”

Nor did they deny the shootings that had gone on in the villages.

“If any man, woman or child goes out into the field at night in the Summer and picks a single ear of wheat, then the punishment according to law is death by shooting,” the Communists explained to me.

And the peasants assured me that this was true.

The greatest crime in Russia is the taking of socialized property and murder is regarded as a mere relic of capitalist upbringing and comparatively unimportant compared with the sin of the mother who goes out to the field at night to gather ears of grain in order to feed her children.”

„REDS LET PEASANTS STARVE’,

oil on canvas, 100x130cm, 2010, Yona Tukuser

„BY GARETH JONES:

One child who denounced his mother to the secret police for plucking wheat at night was made into a great hero throughout Russia.

His praise was lauded in all the schools as the boy who was noble enough to betray his mother for the good of the state!

Tramp! Tramp! Tramp! On I went from village to village, hearing all this news. Everywhere the same tale of hunger and terror.

In one place the folk whispered how some miles away the peasants had refused to give up their cows and form a Communist collective farm.

“So they sent the Red army soldiers to force them,” they told me. “But the soldiers would not shoot upon their fellow peasants.

“What did they do? They called the YOUNG COMMUNISTS in from the town and THEY shot down all the peasants who would not give up their land and their cows.”

Throughout Russia there have been these small revolts, but they have been easily and bloodily crushed.“

“It is not the fault of nature. It is the fault of the Communists”,

oil on canvas, 90x130cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

BY GARETH JONES:

“I was buoyed up by the desire to solve a problem – why was there a famine in one of the richest wheat growing countries in the world? And to each peasant I asked; “Potchemu golod? – why is there a famine?

The peasants replied: “It is not the fault of nature. It is the fault of the Communists.

“They took away our land. Why should we work if we have not our own land?

“They took away our cows. Why should we work if we have not our own cows and if we have to share what is our own with all the drunkards and lazy fellows in the village? They took away our wheat. Why should we work, if we know that our wheat will be taken away from us?

“The Communists have turned us into slaves and we shall not be happy until we have our own land, our own cows and our own wheat again.”

„792 died of hunger, and 135 during the war’,

oil on canvas, 90x120cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

“The famine began. People were eating cats, dogs in the Ros’ river all the frogs were caught out. Children were gathering insects in the fields and died swollen. Stronger peasants were forced to collect the dead to the cemeteries; they were stocked on the carts like firewood, than dropped off into one big pit. The dead were all around: on the roads, near the river, by the fences. I used to have 5 brothers. Altogether 792 souls have died in our village during the famine, in the war years – 135 souls”.

As remembered by Antonina Meleshchenko, village of Kosivka, region of Kyiv

_edited.png)

„Tuesday 19th February 1935, NY Journal - Page 12“,

oil on canvas, 90x130cm, 2010, Yona Tukuser

„When the bread began to ripen, people began to eat the young clams to quench the hunger and they were quickly dying from this. A young man who had eaten a lot of green grain had immediately died in the field (as his belly has simply burst out).“

«Tuesday 19th February 1935, NY Journal - Page 12»,

ttps://www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/thomas_walker/thomas_walker_images.htm

«SKETCH. DAOO, (Prosecutor's Office of Odesa), No. P-7716c. op. 1, case 411, l. 98», 2010, paper, acrylic / 10x15cm

“I Chose Freedom”,

oil on canvas, 90x130cm, 2010, Yona Tukuser

“What I saw that morning … was inexpressibly horrible. On a battlefield men die quickly, they fight back … Here I saw people dying in solitude by slow degrees, dying hideously, without the excuse of sacrifice for a cause. They had been trapped and left to starve, each in his own home, by a political decision made in a far-off capital around conference and banquet tables. There was not even the consolation of inevitability to relieve the horror.”

As remembered by Victor Kravchenko, a Soviet defector who wrote up his experiences of life in the Soviet Union and as a Soviet official, in his 1946 book “I Chose Freedom”.

.png)

„HUNGER, DESPAIR, DEATH IN UKRAINE AGONY“,

oil on canvas, 100x130cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

“Where did all bread disappear, I do not really know, maybe they have taken it all abroad. The authorities have confiscated it, removed from the villages, loaded grain into the railway coaches and took it away someplace. They have searched the houses, taken away everything to the smallest thing. All the vegetable gardens, all the cellars were raked out and everything was taken away.

Wealthy peasants were exiled into Siberia even before Holodomor during the “collectivization”. Communists came, collected everything. Children were crying beaten for that with the boots. It is terrifying to recall what happened. It was so dreadful that every day became engraved in my memory. People were lying everywhere as dead flies. The stench was awful. Many of our neighbors and acquaintances from our street died.

I have no idea how I managed to survive and stay alive. In 1933 we tried to survive the best we could. We collected grass, goose-foot, burdocks, rotten potatoes and made pancakes, soups from putrid beans or nettles.

Collected gley from the trees and ate it, ate sparrows, pigeons, cats, dead and live dogs. When there was still cattle, it was eaten first, then – the domestic animals. Some were eating their own children, I would have never been able to eat my child. One of our neighbours came home when her husband, suffering from severe starvation ate their own baby-daughter. This woman went crazy.

People were drinking a lot of water to fill stomachs, that is why the bellies and legs were swollen, the skin was swelling from the water as well. At that time the punishment for a stolen handful of grain was 5 years of prison. One was not allowed to go into the fields, the sparrows were pecking grain, though people were not allowed.”

From the memories of Olexandra Rafalska, Zhytomir

«Monday March 4, 1936, Chicago American Front page»,

https://www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/thomas_walker/thomas_walker.htm

.png)

„A. GRAZIOSI. Lettres de Kharkov. La famine en Ukraine et dans le Caucase du Nord à travers les rapports des diplomates italiens, 1932-1934. In: Cahiers du Monde Russe et soviétique. XXX (1-2), janvier-juin 1989, p. 59-60.“,

oil on canvas, 90x130cm, 2010, Yona Tukuser

“A week ago a collection service for abandoned children was organized. Indeed, in addition to the peasants who go to the cities because they no longer have hope of surviving in the countryside, there are children who were brought here and then abandoned by their parents, who return to the villages to die. The latter hope that someone in the city will take care of their birthright. […] A week ago, the dvorniki (building caretakers) mobilized dressed in their white shirts, patrolling the city and taking the children to the nearest police stations. […] Around midnight, they begin to be transported by trucks to the Severo Donetz freight train station. It is also where children meet at stations and on trains, peasant families, the elderly and the lonely, gathered in the city during the day. There are doctors […] who make the “selection”. Those who are not yet swollen and have any chance of survival are taken to the camps of Holodnaia Gora, where, in barns and on straw, a population of about 8,000 souls, composed mainly of children, is dying. […] The swollen people are transported on freight trains and abandoned 50-60 kilometers from the city to die without anyone seeing them. […] Upon reaching the unloading sites, large pits are dug and the dead are removed from the wagons“.

„P-470. op. 2, file 2. Information, reports on cases of cannibalism in the villages of Odesa region, on the exhaustion of workers at enterprises in the city of Kherson. 02.03.1933 - 28.10.1933. №9“,

oil on canvas, 90x120cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

„From January 1 until today (February 17), the research revealed that 18 people, mostly children, died due to exhaustion. However, there are no accurate data on mortality; For example, the study found that a 7-year-old child died at the household of collective farmer Nogaichenko, no one knows about his death.

The condition of collective farmers was checked at home:

Fomenko Prokhor - family of 7 people, children aged from 7 months to 8 years. Everyone is exhausted, lying on the stove. When I turn to Fomenko's wife and ask: „What are your children sick with?“ - she does not answer, first she starts to cry, then curses: „How long will you torture us with hunger.“

Zashlyakhovski - a family of 5 people. Four children aged 8 months to 8 years. His wife died recently on the road while walking. The children and the father are swollen with hunger. There is absolutely nothing in the apartment - everything has been sold off. Cold. The family ate their dog. Zashlyakhovski asked that they take his children away somewhere and save them, because he will die. Then he added: „I used to be in the Red Army once, I was a revolutionary, and now I'm dying of hunger.“

.png)

„A 21st century view of a document./ „Projection of a metamodern method for the study of the famine in Bessarabia in 1946–1947, reflected in historical painting“, Yona Tukuser, „Historical Review“ magazine, 2020, pp. 123-124“,

oil on canvas, 90x130cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

„Prodrazverstka“ (food apportionment) is a policy of securing food supplies by taxing the peasants in the form of grain and other foodstuffs in the Russian Empire, the Russian Republic and the RSFSR. It was started by the government of the Russian Empire in 1916 and continued by the Provisional Government in the form of a „bread monopoly“, with the state distributing its stocks. In 1917, a circular was issued with an order for „armed seizure of bread from large owners and all producers from the villages that are located near the railway stations“. In connection with the introduction of the food dictatorship in 1918, the Food Army of the People's Commissariat of the RSFSR was created, consisting of armed food detachments.

„Prodrazverstka“ is part of the policy of „military communism“ and is carried out by forcefully confiscating bread and other products from the peasants according to the established norm of „Prodrazverstka“. Thus, it becomes clear that the „Prodrazverstka“ applied in the Soviet Union is a product of the tsarist and the Provisional Government.

A. Graziozzi believes that the famine should be considered as an integral part of the state's war with the peasants: „In May 1921, Osinsky wrote to Lenin that the local leaders

saw the peasant as a natural saboteur in relation to the Soviet regime and they consider the tax in the form of food a temporary trick to pacify the village“.

According to Berdyaev, the dictatorship of the proletariat turns out to be a dictatorship over the peasantry, which commits cruel violence against the peasants, as in the case of forced collectivization with the creation of collective farms. And here he adds: „But the violence against the peasants was committed by their own people, who came out of the people's lowlands, not by the privileged „white bone“. The unheard of tyranny, which is the Soviet system, is subject to moral judgment.“

„P-470. op. 2, file 2. Information, reports on cases of cannibalism in the villages of Odesa region, on the exhaustion of workers at enterprises in the city of Kherson. 02.03.1933 - 28.10.1933. №1 / Sunday March 3, 1936, Chicago Herald & Examiner p.3“,

oil on canvas, 90x130cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

„Confidential. To the chairman of the Regional Executive Committee. Odessa. A special report.

In the village of Arkhangelsk, on February 23, 1933, teenagers Terebilo Vasily - 12 years old and Terebilo Nikolai - 13 years old, whose parents: father - Terebilo Mark, a poor collective farmer, who is in the Kherson prison for storing gold currency, stepmother - Akulina Terebilo, who went in an unknown direction after the arrest of her husband, - invited a 12-year-old boy from the same village Teterya Vasiliy, the son of a poor man - an individual worker, to spend the night with them.

During the night, Terebilo Vasily and Terebilo Nikolai slaughtered Teterya Vasili, then cut out part of his chest and entrails, boiled them and ate them.

Teterya was slaughtered in the house owned by Terebilo, in bed, in the same place where he

slept. The instrument of the crime was a kitchen knife.

The crime was discovered by the local militiaman Drobnich, who was in the village of Arkhangelsk.

Pre-trial proceedings are being conducted on the case by the Regional Police.

Head of Militia Department, Odessa Region - Petero. Head of Special Department – Barski.“

«Sunday March 3, 1936, Chicago Herald & Examiner page 3»

https://www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/thomas_walker/thomas_walker_images.htm

.png)

„P-470. op. 2, file 2. Information, reports on cases of cannibalism in the villages of Odesa region, on the exhaustion of workers at enterprises in the city of Kherson. 02.03.1933 - 28.10.1933. №47 / Friday March 1, 1936, Chicago American“,

oil on canvas, 90x120cm, 2013, Yona Tukuser

„Urgent. Highly confidential.

At the Znamenka railway station, 5-10 people die every day. All these people, traveling from all corners of the USSR, hundreds stop at the Znamenka station, acting as a switchboard, waiting for several days for their turn to get on the train, and without means of sustenance - they die of exhaustion.

Both we and the railway station do not have food resources to organize at least a minor food station at Znamenka station, which will greatly ease the situation for us, as such cases have an extremely negative effect on other passengers.

March 19, 1933“.

«Friday March 1, 1936, Chicago American Front page»

https://www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/thomas_walker/thomas_walker_images.htm